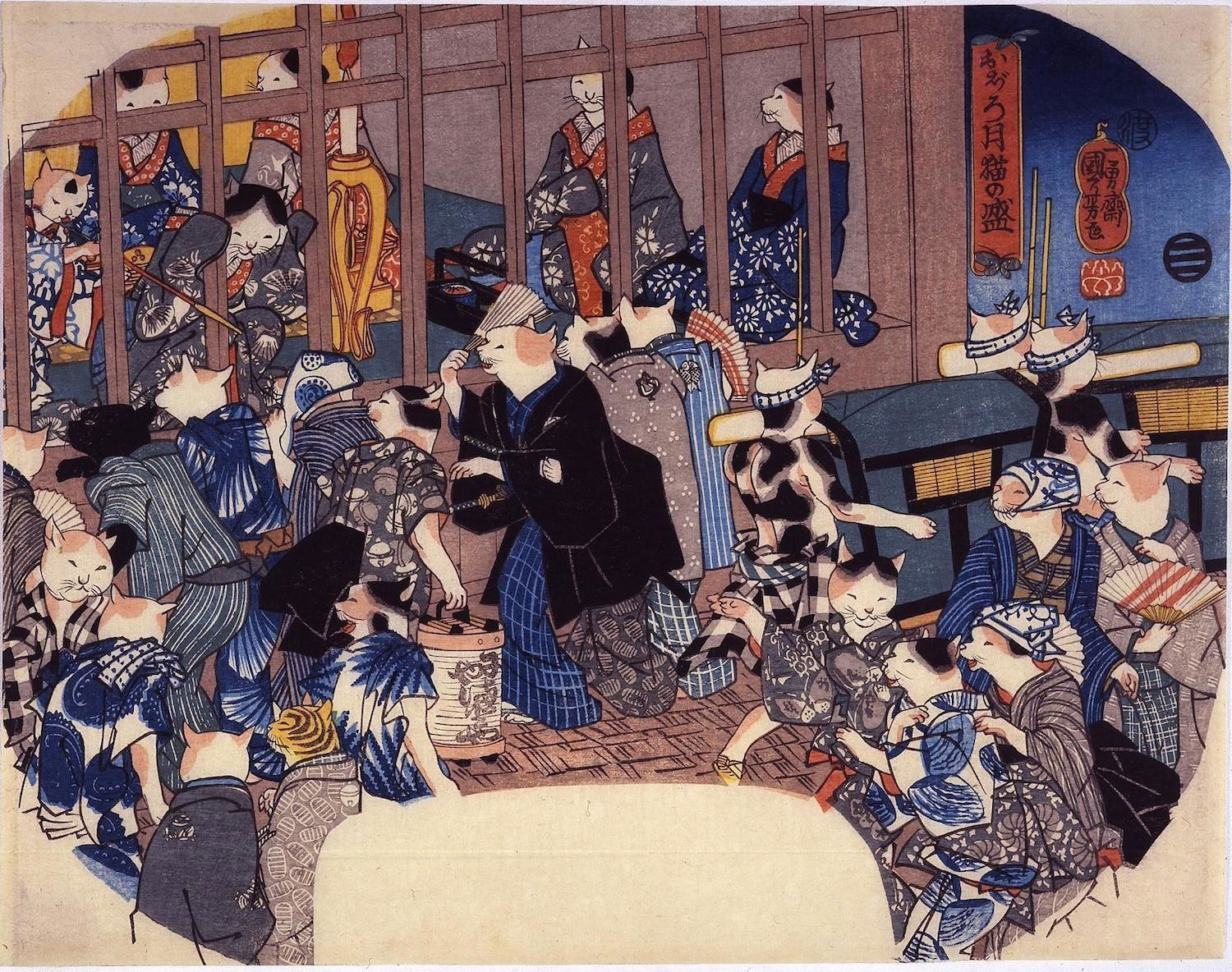

Cats Suggested As The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, (1850), woodblock print. Source: WikiArt

Fifty-five cats appear in this triptych print by the Japanese illustrator Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797–1861). One of them crawls out of a basket; a few catch rats; others eat fish. They look terrific but is there a reason behind the illustration? To my eye, the image is clearly more than just a series of sketches. It makes me wonder do their actions carry some kind of meaning, or are they simply the work of a man who loved cats? To answer these questions, it's best to travel back to a time long before the print was made and discover where this obsession with cats all began.

In the sixth century, Buddhist monks travelled from China to Japan. On these journeys, they brought scriptures, drawings, and relics – items that they hoped would help them introduce the teachings of Buddhism to the large island nation. They also had something else on board that would leave a lasting impression; to guard over their possessions, they travelled with domesticated cats. They believed that these creatures could bring good luck and that they would be able to guard the sacred texts from the hungry mice that had stowed on board their ships. While the lasting influence of Buddhism was certainly something that the monks had hoped for, it is unlikely that any of them could have imagined just how big an impression their feline companions would also make on the country.

Today, cats can be found nearly everywhere in Japan. From special cafés and shrines to entire cat islands. Indeed the owners of one Japanese train station were so enamoured with their cat that they appointed her stationmaster. It’s fair to say that the country's feline fixation knows no bounds. And yet, this obsession isn't a recent phenomenon, it can be found throughout all aspects of the country's history, and it doesn't take long to find some really fascinating examples of it.

Perhaps the most interesting ones occur during the Edo period (1603–1868). At this time, the country was witnessing massive economic growth. Under the strict control of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the country was finally unified. Civil unrest ended and an unprecedented period of peace emerged. This period brought great prosperity and new cultural and social developments. A new wealthy merchant class emerged – and they were eager to spend their money on things like theatre, literature and art.

One of the most popular types of art at the time was ukiyo-e. Today, these woodblock prints hang in dimly lit museums and are considered to be delicate and precious works of art, yet, during the Edo period, they were pure pop culture. Bought by the newly rich, they depicted the pleasures of the country’s new hedonistic ways, and they celebrated the popular culture of the time. People would decorate their homes with scenes of beautiful geishas or the stars of kabuki theatre; they would collect travel prints, portraits of wrestlers and even erotic images. For illustrators, the more popular the subject matter, the more likely it was to sell.

Ukiyo-e prints defined the era, and one of the last great masters of the art form was our cat-fanatic friend Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Few can match the energy and immediacy of Kuniyoshi’s work. He was highly skilled and effortlessly proficient, producing hundreds of prints that remain striking to this day.

Originally, he studied under the celebrated printmaker Utagawa Toyokuni (1769–1825), and his early work is somewhat reminiscent of his style. Being the son of a silk-dyer meant that Kuniyoshi’s early life was not an easy one. His poor background meant that it took time for him to establish his career – but, eventually, he found success through a series of illustrations based on a popular collection of warrior tales.

Two prints from the series 108 Heroes of the Popular Water Margin. Left: Saienshi Chosei (c. 1827–30), woodblock print. Right: Seibokukan Kakushibun (c. 1827–30), woodblock print. Source Ukiyo-E.org: 1 and 2

Much of his thirties were spent drawing heroic figures, and, as his reputation grew, he was afforded more opportunities to broaden the scope of his work. He illustrated many genres – drawing everything from landscapes and animals to ghostly apparitions and scenes from popular Kabuki theatre.

The Story of Nippondaemon and the Cat (1835), woodblock print. Source: Teleport City

Like most Japanese people, Kuniyoshi loved cats, and when he became a teacher, his students noted that his studio was overrun by them. His fondness for felines crept into his work, and they appear in many of his finest prints. Sometimes they crop up as characters from well-known stories; other times, they are beautifully expressive studies.

Left: Cat and Goldfish from the series One Hundred Tales, (1839), woodblock print. Right: Four Cats in Different Poses (1861), woodblock print. Sources: 幕末ガイド and WikiCommons

Occasionally Kuniyoshi would find fun, inventive and unique ways to draw them. His series Neko no ateji is a perfect example of this. Here he has cats form shapes that spell out the names of different types of fish. The characters are in kana – the syllabic Japanese script. This type of work demonstrates the lighthearted and playful nature of Kuniyoshi, and it helps to confirm his reputation as a very likeable and affable man.

Left: Catfish (namazu) なまず, (1841), woodblock print. Right: Pufferfish (fugu) ふぐ , (1841), woodblock print. Sources: Kuniyoshi Project

Sometimes Kuniyoshi would depict cats in fully anthropomorphised form. They would walk around in costumes doing everything that humans do. While these types of illustrations are fun to look at, there is also a deeper reason for their existence. During the early 1840s, the Tokugawa Shogunate believed that their political hold was starting to loosen. To reassert power they introduced the Tenpō Reforms. These were a series of strict and oppressive policies that aimed to strengthen their control. The Reforms included a ban on representations of kabuki actors, courtesans and geisha. For the Tokugawa Shogunate, these professions represented luxuries that society could not afford and – by depicting them – artists were said to be purposely provoking society through subversive ideas.

To get around this censorship, Kuniyoshi would often illustrate famous kabuki actors in animal form – frequently hiding small clues that could hint at an actor's true identity. While the Reforms certainly brought about many limitations for illustrators, they also pushed them to think up new and inventive ways to communicate with their audience. Kuniyoshi's prints were hugely popular at the time, and kabuki fans enjoyed trying to solve the visual clues that helped them identify each actor.

Hazy Moon cat, Sheng (1846). Source: LETS

In the late 1840s, they ceased enforcing the Reforms, and Kuniyoshi began to illustrate more traditional prints of actors once again. Yet his playful nature remained – and so too did his love for cats. Stories about the illustrator often mention how he would spend his days working with a kitten snuggled up in his kimono, and he also frequently suggested to his students that they create images of cats. Indeed, after the success of Kuniyoshi, the number of cat illustrations in ukiyo-e prints seems to have increased significantly.

All of this eventually brings us back to our original print and its fifty-five cats. What is the story behind it? Is it simply a study – or is it a scene from a kabuki performance? Could it be a puzzle – or is it the result of oppressive censorship? First and foremost, I believe, that it is an illustration that comes from a man who had a unique ability for observing and drawing cats. He catches the nuances and the subtle movements of each one of them perfectly. They're all distinct and every one of them looks as though they have a personality of their own. This is certainly Kuniyoshi's intention. The work is called Cats Suggested As The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and each one represents a station on the road that links Tokyo to Kyoto.

Kuniyoshi's illustration is a fun spoof on Hiroshige'sThe Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1833–34). Hiroshige's impressive series was the biggest-selling collection in the history of ukiyo-e and, even a decade on, Kuniyoshi's take would have still felt relevant.

The Tōkaidō – or 'Eastern Sea Road' – had fifty-three different post stations along its route, and these provided stables, food and lodgings for travellers. Where Hiroshige captured each of these through a series of different landscapes, Kuniyoshi decided to show them through cat puns. For example, the forty-first station of the Tōkaidō is called Miya. This name sounds somewhat like the Japanese word oya (親), which means 'parent'. For this reason, the station is shown as two kittens with their mother (below-left).

Another example is the fifty-first station. This stop is called Ishibe, and its name sounds similar to the Japanese word miji-me (ミじめ), meaning 'miserable'. To illustrate this, Kuniyoshi drew the town as a miserable looking cat (below-right). Its body looks frail, its hair is coarse, and it yelps out with a wretched purr.

While the fun of these puns is a little lost in translation, one can easily imagine how great they must be for a Japanese speaker familiar with the Tōkaidō. For non-native speakers, Kuniyoshi's prints remain a fascinating reminder of just how inventive ukiyo-e can be, and his illustrations continue to be a joy to behold. At a time when cats dominate so much of our online lives, it's great to remember that their appeal was just as prominent in the closed-off corners of nineteenth century Japan. Perhaps our life today isn't that far removed from the world of ukiyo-e. Who knows what great creativity will be inspired by the cats of the future!